Early December 2011, and it is a decade to the day (8th December 2001) since I received my first Timefactors designed and produced wristwatch from Sheffield which of course was the subject of an enthusiastic review. The timepiece in question was the Speedbird PRS-1 which as a watch, I have revisited personally over the last month or so with a great feeling of nostalgia both in terms of the watch itself and indeed the time at which it was conceived. Some readers of this review may be new to watch collecting or simply reading as they may be in the market for a new watch. For many of us however, particularly those with a propensity to buy and keep watches with a ‘meaning’ to them, then occasions will occur where we sit, take stock and maybe think back over our watch collecting years and the events or situations that we associate with a particular timepiece.

For me, the original Speedbird evokes so much – the beginning of a new era of ‘micro-manufacturers’, personal involvement during its design, the first watch for a long time which truly excited me (read my review for confirmation of this) and the list goes on. Certainly, the Speedbird has been with me through thick and thin, ups and downs, trials and tribulations. Thus, as well as the whole concept of such a watch as the Speedbird, there is also the fact that it happens to be the timepiece that I have owned for the longest; it takes ten years to build a decade’s worth of memories and feel for a watch and in the case of the Speedbird, all I can do is sit and smile when I glance down at it. When I owned Rolex et al watches in the past, more often than not they had lost their lustre and were sold within three years.

As I write this review I am of course wearing the PRS-25, but for reasons of nostalgia I have the PRS-1 sat in its box on the desk. It would seem therefore that Timefactors created a ‘winner’ (certainly from my point of view) back in 2001. Since then of course, Timefactors has, in my opinion produced other winners. The decade has seen chronographs, divers, general service watches both quartz and mechanical with others currently under development. What is undoubtedly true of many Timefactors timepieces is that they have served and continue to serve a market hungry for re-editions, homages or simply for watches which allow the wearer a taste of the past with the reliability of the present and with a dash of originality to boot. And they have served that market well over the years, with a quality to price ratio which I have praised personally in reviews past.

Before I sat down to write, I was concerned that this review would be difficult to author – after all, I have a taste in wristwatches which tends to maintain a somewhat constant theme – utility, military, issue with of course the addition of a NATO strap on just about everything I wear. No doubt there is a constant theme to the watches themselves; yes, they are different from each other but the basic theme is there. However, as I have alluded to above, the ten year mark in the history of Timefactors watches has without doubt some significance for me personally; the subject of this review marks that anniversary at a time when there is a proliferation of small brand wristwatches, the internet has become a crowded and competitive wristwatch marketplace and of course the economic climate may not be conducive to non-essential or luxury purchases. Before we continue, perhaps I should address one point raised above or rather let the PRS-25 address it – this is not a small brand wristwatch, this is a Smiths.

Overview

This is a Smiths. This is a Smiths Everest to be more precise. At first sight readers would be forgiven for mistaking the new Smiths for something perhaps more well known in the watch world. As with any successful design, others will follow based very closely on the original. Thus, if we hark back to the mid 1950s then the first of the Rolex Explorer series made its appearance and as is well known, this watch continues to be a highly popular design.

Many watch companies over the years have imitated the classic Explorer format, certainly with regard to the dial. Certainly in recent years some of the smaller watch companies have manufactured enlarged versions of this iconic classic. So, we have most recently (2008) had the Mk II Vantage equipped with date and ETA movement housed in a 39mm case; prior to that of course were Sandoz Explorer types, similarly equipped and available primarily from South East Asian sources. What these two watches had in common was the use of a flat sapphire crystal which was of course very practical and true to current Rolex Explorers but didn’t perhaps capture the vintage feel of a watch with an acrylic crystal.

Readers of my watch reviews may have read one of the earliest of such which featured the Zeno Explorer; this watch went on to become something of a classic itself, with the final production examples being equipped with an ETA movement. The original Zeno Explorers were of course powered by a standard Miyota automatic calibre and this performed very well. The Zeno explorer was extremely close in proportion to the original Rolex 1016 and very close in looks – 36mm diameter and of course a matt black 3,6,9 dial without applied indices. For many, the main negative of the Zeno was the size, particularly at a time when a ‘normal’ wrist watch size was exceeding 40mm. What this watch did represent undoubtedly was superb value for money – GBP £80.00 or so when it first became available. Alas, the Zeno has not been available for sometime and nothing has been introduced to market to take its place.

Where therefore does the new Smiths Everest fit into all this? I would say at the outset that this watch is catering for more than one requirement should the purchaser be looking for an Explorer type watch. More of that later. For me personally, it is exciting to see another new watch with the Smiths name upon its dial, furthermore for this model to be christened ‘Everest’ seems so appropriate given the conjecture, stories and myths relating to watches that were indeed worn to the summit of Mount Everest over half a century ago. It would seem at the outset that the new Everest has the potential to fill a gap in the market (with the Zeno Explorer and Mk II Vantage no longer available), in addition to being a watch which might pull together elements of many Explorer type timepieces into a cohesive whole.

Before we look at the watch itself we must revisit briefly the brand name of Smiths. In resurrecting this historical British brand, Timefactors has equipped itself with a very powerful tool but at the same time I do feel that it is extremely important that the Company produces wristwatches worthy of such a name. Readers of my Smiths Military watch review will appreciate just how excited I was at the introduction of this superlative wristwatch. It would be easy to repeat myself but I do feel it worthwhile and appropriate to reproduce one section of that review here:

A Very Brief History of Smiths

Smiths, the company, can trace its roots back to 1851 and boasted a long and diverse history, the whole of which is beyond the scope of this review. Concentrating on Cheltenham itself, the original factory dates back to the latter part of 1939 with production of aviation clocks. As a slight aside, not long after I had become aware of Smiths watches early on in my interest in timepieces, I had heard more than once that ‘some of the movements were actually Le Coultre’ or ‘that movement was designed by Le Coultre’. What is certain is that literally just prior to the Second World War, Smiths acquired the dies and engineering information necessary to manufacture aviation clocks which had up until then, been supplied by Le Coultre. Thus, aviation clocks made to a design by Le Coultre were, by 1940 being manufactured in the newly built factory at Bishop’s Cleeve (factory CH1). In later decades and in the case of wristwatches however, any relationship with Le Coultre extended only to certain design aspects/influences and the fact that Smiths took on an ex Le Coultre employee as a director. The watch factory also employed ten or so Swiss nationals who were fully trained and highly skilled watchmakers. In those days, manufacture meant manufacture with, for example, hairsprings being manufactured onsite (or more precisely, by a company Smiths had set up in a converted Grange a few hundred yards to the north of the main factory). Interestingly enough, I recently met an elderly lady who was in fact in charge of the workforce at the hairspring factory at the Grange for a time; though we didn’t have the opportunity to talk in detail about her days with ‘British Precision Springs’, I could tell from what she was saying that she looked back on that era with great affection.

As the factory site was developed and expanded during the Second World War, then production of 8 day aircraft clocks was undertaken in the second factory (CH2) along with watches. Mainstream sales to the civilian market commenced around 1947. What of course we mustn’t forget is that the product offerings from Smiths covered an increasingly wide spectrum as time progressed. Thus, we can include automatic pilot units, RPM Indicators, Air Speed Indicators, fuel gauges, head up displays, autoland systems amongst others. Most of the aforementioned were produced at the same time as a wide range of wristwatches for public consumption and from the same (ever expanding) site at Bishop’s Cleeve. In the past, I had only ever considered Revue Thommen as a company which produced wristwatches as well as aircraft instrumentation; however, on my doorstep was factory which between 1947 and 1971 produced a wide range of wristwatches, some of them of a very high quality.

In terms of wristwatches, then from 1947 onwards Smiths produced catalogues on a yearly basis and the highest grades of the range were produced at the Cheltenham factory. A small range of gents and ladies calibres were produced onsite with a varying jewel count; one series of automatic was available by the late 1950s with heavy design influences from IWC. Small seconds, indirect centre seconds and date options were available. Smiths themselves were not averse to the type of advertising that became very prevalent in later years in terms of product association –

A 1953 advertisement refers to the Everest Expedition of that year

I must admit that I take great pleasure in the fact that such watches were indeed utilised in the adventures of the 1950s; yes, Rolex have a claim to the Explorer being used on the Everest Expedition and this review is not intended to debate such; for me however, I can garner a warmer feeling from the knowledge that the factory I know and have lived so close to played a part. If I could find good examples of models Everest and Antarctic I would snap them up in an instant – truly historic and romantic association! Smiths watches (from Bishop’s Cleeve) of the period were labelled De Luxe; prior to 1952 the dial simply stated Smiths. Later designations were Imperial and Astral and it is interesting to note that although a range of ‘Everest’ watches was introduced in 1954, the name didn’t appear on dials until ten years after the Expedition itself. The Antarctic range, whilst promoted within illustrated catalogues never had the name adorned on dials. I personally find the advertisements of the era wonderful reading in their innocence, simplicity and period phraseology.

The Horological Journal of September 1965 contains an article describing the watch manufacturing operation at Bishop’s Cleeve. In addition to mentioning the manufacturing tolerances adhered to, reference is made to the timing of movements; I find it fascinating that the Smiths movements of the mid 1960s were as a matter of course timed and adjusted for either 8 or 12 days in three positions. I would not know which other mainstream manufacturers undertook such timing for all its production. It is stated also that the automatic calibre was assembled totally by hand, likewise stopwatch calibres. Even then, the handwind calibres were assembled in the main by hand with final positioning of sub assemblies assisted by vacuum fixtures and air tools. The overall picture is of a local workforce involved in the careful manufacture of a high quality product with quality control taking place at all stages. If I had known such a long time ago I would most certainly have held Smiths in higher esteem than perhaps I did. All after sales service was carried out at Bishop’s Cleeve too; repaired movements being timed for six days in three positions.

Not since 1954 has a Smiths Everest been introduced and not since 1963 has a new watch been introduced with ‘Everest’ adorning the dial, let us now consider the 2011 Smiths Everest.

Packaging

Much to my delight, Timefactors have chosen to concentrate on the watch as opposed to the packaging and ‘bits’ that come with it. Thus, presentation consists of a black zippered travel case, an instruction leaflet, guarantee card, polishing cloth and Timefactors pen no less. Plenty enough in my opinion (and actually quite generous give the price point in question); the travel case itself should prove very useful for storing the watch when not in use and indeed for transportation should the owner for example take an extra watch on holiday. I must pick up on the polishing cloth that is included; I wouldn’t normally give much store to a simple polishing cloth but this one would appear to be indicative of the thought that goes into new Timefactors releases; it is sizeable at almost a foot square and is made of a wonderfully soft microfibre material – the stealthy stamping of the Timefactors logo and brands personalises it and I can attest to its ability to give a watch an effective wipe over for photographs or of course to remove everyday watermarks and smudges. A nice inclusion.

For me, if there is an important part of packaging then it is the protection the watch itself is given during and after manufacture. I like to see plastic coverings here and there – no doubt this is a psychological quirk of mine but in any case the Everest does not disappoint. The bracelet is totally cocooned in protective plastic and the watch itself has good sized protective plastic stickers to both the case back and of course the crystal. Brand new and fresh – this is how the watch appeared on unzipping the travel pouch and the first aspect of the whole experience to get top marks from me.

So what of the ‘wow’ factor on first sight of the Smiths Everest? First impressions mean a lot to me and on first sight of this new introduction my reactions were what have become typical for me on seeing a new Timefactors watch for the first time – a smile and a minute or so of gawping at the latest creation.

The original Speedbird impressed me with its finesse upon first sight – the Everest immediately struck me as more of a bully; a serious, ebullient sports watch with its brand name boldy displayed. How would I feel about it on closer inspection?

When I reviewed the Zeno Explorer over a decade ago, I commented on the possibility that it would be difficult to pass judgement on what I saw (and continue to see) as a somewhat generic case design. Time has moved on and so indeed has my approach to analysis of what makes a ‘good’ watch case.

Undoubtedly of course, the Smiths Everest is very much inspired by the case of the grandfather of them all, that being the Rolex Oyster with its curves and polish. Nobody will produce (counterfeiters aside) a case that exactly matches the Rolex and indeed this may raise the question as to why would one need to anyway? Rolex themselves have produced variations and updates to their cases, particularly of late.

Thus, perhaps we should not attempt to compare directly and indeed, why should we? After all, (and certainly in the case of Timefactors) the smaller manufacturers sell themselves and their products on the basis of improving on the original or at least addressing some of the issues that might preclude us from purchasing the same – size comes to mind and of course price.

As with many, if not all Timefactors watch projects, the details of the Smiths Everest were made public and the idea put forth on the Timefactors watch forum. The precedent set by Timefactors over the years has always been one of high quality and value for money and the idea of an Explorer type watch from this stable was met with considerable enthusiasm. It would seem therefore that the appetite for a watch which was no doubt destined to at least look like many before it was there and I would suggest that the challenge was not inconsiderable in terms of getting the watch case ‘right’. Certainly from my point of view, any wristwatch that comes to market after a succession of similar watches have already done so must offer something with which to differentiate itself both from the original of many decades ago and perhaps more importantly from that aforementioned succession. In the case of the Smiths Everest, that differentiation indeed starts with the case!

Case

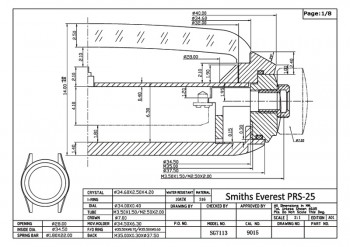

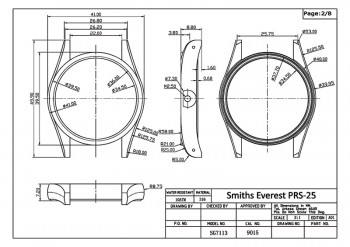

Firstly, we must give consideration to the dimensions of the 316L stainless steel case. As is usual for Timefactors, the original drawings were published when the watch was released on 29th November 2011:

As can be seen the classic Oyster dimensions have been upsized somewhat as per the following specification:

| Total case diameter: | 41.00mm |

| Diameter across bezel: | 39.50mm |

| Lug to Lug distance: | 49.90mm |

| Bezel width: | 2.50mm |

| Height of case band: | 7.20mm |

| Height of bezel: | 2.40mm |

| Total height: | 14.50mm |

| Lug width: | 22.00mm |

| Anti-Magnetic Rating: | 4800 A/m |

| Water Resistance: | 100m |

From my point of view, the two most important dimensions given the increase in case diameter from the ‘classic’ Oyster 36mm are the height of the case band and the bezel width; these are two areas where things can go wrong as far as the watch looking ‘right’ is concerned. Thus, the case band height gives an opportunity to incorporate a meaningful curve to the side of the case and the bezel width plays an important part in making sure watch is neither ‘all dial’ or ‘no dial’ so to speak.

If we address the case band firstly then the curvature I would expect in such a case design is there in all directions – the watch is proportionally ‘fat’ to its diameter and this has afforded Timefactors the opportunity to incorporate curves to the case side which in this case(!) are excellent and show that thought has been put into the whole project. As a side (but important) note Timefactors always use freshly designed cases – nothing off the shelf here and this does show (incidentally, the Everest has drilled lugs for ease of bracelet removal). The vertical curvature integrates beautifully with horizontal curvature as we move from the widest part of the case to the lug tips; given the superbly polished case sides then the whole effect is really quite mesmerising as one turns the watch over or moves it from side to side. Thankfully the case band is not too fat (think Tudor Chrono Time) as of course we need to add a case back, bezel and crystal to the equation.

The bezel: as can be seen in the case drawings above then this is not an integral part of the case – it is a separate affair, precisely machined and set into the case atop a gasket which goes some way to ensuring the stated 100m water resistance. As mentioned earlier, the width of the bezel can (in my opinion), make or break the whole look of a wristwatch, particularly if the idea in the first place is to recapture the spirit of the first of the line. Thankfully, the Everest gets this aspect just right – the (correct) highly polished bezel is sloped at the right angle and has a width which would seem to complement the case diameter perfectly. When wearing the watch one isn’t conscious of vast expanses of polished steel atop the watch, nor does the dial overpower the whole affair; the balance is aesthetically just right. Thus far then all proportion seems to be correct but of course there is that all important aspect of lug width. Indeed we are dealing with what is essentially a 40mm wristwatch, thus at 22mm the lug width of the Everest should be fine. I had considered the MK II Vantage some time ago which dimensionally was extremely close to the Everest but featured 20mm lugs. There was always something I found not quite right about the MK II and on seeing just how ‘right’ the Everest looks proportionally I now realise that it was the combination of the 20mm lug width combined with lugs that were ‘overfat’ when viewed from above; thus whilst the Everest is most certainly a scaled up version of the classic case that most of us will know, it has been scaled up correctly in terms of how the watch looks from all angles – nothing looks ‘wrong’.

Turning the watch over what is immediately striking is that the Everest has an almost perfectly flat case back; the only external depth is to allow for the six removal key slots.

The thickness of the case itself no doubt makes this possible but what this design means is that combined with the sweeping curve of the case when viewed side on, the watch is so very comfortable to wear despite its relatively tall lug tip to lug tip dimension of just on 50mm.

As a wearer with relatively small wrists, such a lug to lug length would normally be ‘pushing it’ for me but in the case this is not of issue at all. I am thankful that Timefactors didn’t specify a ‘bubbleback’ for the sake of it; I am further thankful that traditional case opening slots were specified as this will make life easier for those who may wish to ‘tweak’ the movement themselves.

The case back itself is of a fully polished finish with the following text:

PRS-25

SMITHS

001/11

WR 100 METERS

The above inscriptions tell us all we need to know with the ‘Smiths’ script being proudly large. Regarding the serial number then this can simply be deciphered as watch number 1 of the year 2011 (my example is serial 007/11). Polishing is mirror-like and the engraving is deep enough to allow many many years of wear before, if ever, it became worn to illegibility. For those who prefer to wear their watch on a NATO strap then be prepared for quite rapid marking of the case back – polished finishes quickly suffer from ‘NATO burn’ although for those so inclined, there are stickers available to protect the finish from the ravages of NATO nylon.

I have mentioned above the polishing to the sides of the case – after close inspection it can be stated that it has been superbly executed; it is a truly beautiful finish which accentuates all the curvature incorporated into the case design. I cannot find fault in this area and this would extend to the bezel too. Obviously for consideration is the finish to the tops of the lugs. These are finished with a medium grain concentric brushing which is of course ‘correct’ for this type of watch and from a practical perspective will stave off micro scratches to a good degree. The brushing is even, uniform and neatly applied – remaining where it should be and not trespassing into polished areas in any way. The lug tops are of course the only part of the watch which is brushed and on the subject of the lugs it can be seen that the tips have been flattened off just enough to remove the sharp ends that Rolex have been famous for in the past (as an aside, I actually prefer the sharp ends). Thankfully, such flattening hasn’t been overdone to the extent that it spoils the flow of the case shape.

The Smiths Everest is specified for 100m water resistance; for me, this is more than enough, hopefully I will never be that deep under water and should I be so then it is unlikely that I will be concerned as to whether or not my watch is up to it. To aid this degree of impermeability the watch is equipped with a screw down crown. Not too large and not too small, the 7mm diameter is perfectly (once again) proportioned to the size of the case; finish is all polished which matches the case side to which the crown is attached and the serrations are crisp, well cut and deep which will of course aid hand winding should that ever be necessary. Unscrewing or screwing down the crown takes a good four/five revolutions as far as I can measure and for many wearers this will give an extra feeling of security – the crown screws down smoothly and it is very easy to catch the chunky and deep threads.

When off the threads, there is very little crown wobble and everything seems snug and secure. A nice touch is the indentation which has been machined into the side of the case around the threaded tube – this serves to ensure that once screwed in, the crown sits nicely into the side of the case without any unsightly gap (which can occur if tolerances are even very slightly out). At this juncture, there is absolutely no doubt in my opinion that quite some thought went into getting the case of the Smiths Everest right. A millimetre here or there could have made so much difference aesthetically and I am certain that it is no mean task to upscale a classic design whilst retaining proportion and beauty. ‘Beauty’ – there is a beauty to this watch but given the size of the creation I would suggest that it is a brute beauty; this is most certainly a solid chunk of metal – everything about it thus far feels solid, machined, honed, hewn – to use but a handful of adjectives. Of course, structurally there is also the watch crystal to consider, but this is also a hugely important aesthetic element of design which I shall consider with the dial and hands.

Crystal, Dial and Hands

What the Zeno Explorer got right was the combination of a classic ‘1016’ dial (3,6,9 dial, matt, without applied metal indices) combined with a domed acrylic crystal. What the MKII Vantage got wrong (in my opinion) was the use of a combination of the classic dial (albeit with a date) and sapphire crystal. From a practical perspective then yes, a sapphire is of course a lot harder wearing than acrylic, but in the case of a watch which is aiming for the vintage look and feel then I feel that the right choice is the ubiquitous acrylic; it can after all be polished when the inevitable scratches appear. I feel that the use of a sapphire crystal on the Smith Everest would have been a big mistake in terms of design and aesthetics and of course it may have made a difference to the retail price of the watch.

The Smiths Everest therefore, utilises an acrylic crystal. When it comes to acrylic, then even that can be done wrongly – they come in various thicknesses, profiles, densities and so on. That with which the Everest is equipped is superb. Thus, as well as being domed to its top, there are no slab sides to be seen, the edges of the crystal are themselves arced to where they meet the bezel line. More curves to admire! Vertical edges of such a crystal are of course necessary to ensure sealing against the elements but in this case they are hidden away and abut the inner hidden lip of the bezel.

Curved edges, whilst being very pleasing will cause some distortion at dial’s edge unless the watch is being viewed straight on – to me this is part of the charm and character of such an arrangement; this distortion is apparent on the Smiths but the radius of the outer crystal curve is such that distortion is kept to a more than acceptable level – meaning that one can very much choose when one wishes to experience the sight of a dial numeral being ‘melted’ and sliding its way into the side of the case.

Just tip the watch from side to side and the effect is interesting to say the least.

Structurally, the crystal comes in at 2.5mm in thickness at dial centre. I can assure any reader that this is a ‘good’ thickness; tap the crystal with a knuckle and there is a reassuring thud as opposed to the tinny tinkle of a thin, flat acrylic. The crystal adorning the Everest reminds me very much of that of the early Rolex Sea Dweller I wore some thirty years ago. It suits this watch perfectly and of course matches the chunkiness of the rest of the piece. Given the inherent thickness of material available, replacement would seem many years away as I am certain it would be quite difficult to crack this one and of course such thickness ensures that polishing the inevitable scratches out could be done on a regular basis without worry of wearing a hole in the crystal!

So, my impressions of the shell of the Everest are extremely favourable; the whole case construction seems extremely strong and well engineered with much aforethought having taken place before construction. Without doubt, and viewing things from my quarter, then this watch has been built for long-term use without worry – it is substantial, solid and hugely practical. But what almost literally shines through all this solidity is beauty; it is not a thug like case in any way. Despite generous proportions, the curves and grace are there for which I have long admired the earlier Rolex Oyster cases. At this point therefore we must delve deeper, under the perfect crystal to the dial and hands and then further still to what beats within the watch.

The Zeno Explorer was most certainly a homage to the Rolex 1016 Explorer. It could of course have paid homage to a myriad other Rolex models simply by use of another dial design over that which it featured. The white on black 3,6,9 Explorer dial is a hugely well known design within the watch world, instantly recognisable, eminently legible and it has long been admired for its elegant simplicity. Rolex themselves ‘glitzed up’ the design in 1989 when the Explorer 14270 replaced the 1016 but this was indeed to the dismay of many watch aficionados with the dial becoming glossy black with applied white gold numerals (with luminous fill), and all this below a sapphire crystal. The result was undoubtedly elegant in its way but reflections and glare, previously not an issue with the Explorer were now there aplenty – particularly in bright sunlight. The matt dial with simple white numerals was, and remains the preference for many and that was where the Zeno Explorer scored so highly. What then the dial of the Smiths Everest?

Indeed what we appear to have is a classic 3,6,9 Explorer dial. So, firstly to the layout – yes this is the classic 3,6,9 but it seemingly based on the Zeno dial as opposed to the Rolex affair. In this respect it can be seen that the minute hashes are slightly elongated and indeed are in the region of 3/4 the length of the minute markers. Comment has been passed regarding this design on the Timefactors watch forum with some members postulating that perhaps the minute hashes are a little too long causing the Arabic numerals to too far inboard. What mustn’t be forgotten is that a photograph is a very static thing – on the wrist the overall layout of the dial looks well balanced and whilst indeed the dial does feature relatively long minute hashes, they do not look out of place or balance at all when the watch is wristborne. The dial itself, given the diameter of the Everest is quite an expanse and I feel that shortening the minute hashes and positioning the Arabic numerals/hour batons further out toward the extremities would have resulted in a lot of empty space and a dial which perhaps looked a little ‘stretched’. To my eyes the whole dial layout works well and quite simply looks like the Zeno Explorer’s big brother so to speak. Photographs do not do the dial justice.

So to more detail: the dial itself is of a matt black finish; to be more precise it may be construed as rather a very very dark grey – this is often the case with a matt finished ‘black’ dial. The finish is even and I can make no adverse comment upon it. The minute hashes which I have discussed earlier are applied in a satin white paint; application of such is precise and even with plenty of depth to the colour – under a 10x loupe all is well with nothing untoward that I can see – the paint having been applied generously enough to ensure good coverage. As we would expect from the resurrected Smiths brand then at dial bottom, below the 6, the minute hashes make way for the ‘Great Britain’ moniker, justifiably printed in uppercase and a font size that isn’t shy.

Moving further inboard, the dial features the luminous batons, numerals and single triangle at the 12 which we would expect of the Explorer layout. Firstly to the Arabic 3,6 and 9 and these (as they should be) are fully luminous over white paint using Super Luminova C3 – the luminous compound is thickly applied, pillowed with a little surface sheen. In terms of the font used then this is as it should be in terms of representing the Explorer 1016 and of course the Zeno Explorer – any move away from the original font I feel would have been a mistake, this looks just right and the size too matches the rest of the dial very well. Execution of the hour batons is likewise extremely well done with the Super Luminova remaining within the confines of the white paint as it should and with plenty of depth apparent. The inverted triangle at the 12 matches the size of the Arabics and follows the quality of the other luminised elements of the dial. Thus far, the dial appears to be extremely well conceived and executed, leaving just the logo, (or is it logos?) to consider.

As with the Great Britain script at the bottom of the dial, the Everest is not shy about its brand name which is printed in gloss white below the triangle marker. Thus, the classic Smiths font is used but in a size which ensures that we know that this watch is a Smiths.

I have read one or two rumblings on the internet that maybe the logo is too big – I would say nonsense to this, it is in proportion to everything else about the watch and the watch dial – it is well within the horizontal confines of the 11 and 1 markers and vertically, it takes up far less real estate than for example all the script one would find on a Rolex Explorer dial.

Again, photographs are so static that one tends to focus on things which become less prominent once the watch is on the wrist. The logo is perfectly in keeping. Whereas the Smiths logo is undeniably ‘there’, the model name Everest is, to coin an overused word these days, far more ‘stealthy’ – in fact one would not know that it is there unless one was really looking for it. Thus, a little way above the 6 is the word ‘Everest’ in uppercase lettering and applied in a gloss black. Tilt the watch a little and it can be seen. Why might it have been done this way? I am not certain but it works and works well; certainly this approach would cater for those (such as myself) who prefer as little script on a dial as possible but at the same time it adds a little something; something which in this case is meaningful and a wonderful twist on the whole ‘which watch was worn on Everest?’ debate. The model ‘Everest’ is entirely apt for this wristwatch and the fact that it is applied slightly mysteriously to the dial brings a smile to my face.

Finally to the hands. As might be expected, the Everest features classic Rolex styled ‘sports’ hands. Dimensionally, all hands, in my opinion, are suited to the dial upon which they reside with the seconds hand just kissing the seconds/minute hashes, the minute hand reaching the outer end of the hour markers (but close enough to the minute hashes) and the hour hand reaching a little inboard of the same. It works. The hands themselves are relatively ‘stubby’ with the minute hand being wider than the hour hand. This is somewhat representative of later Rolex Submariner models for example and does not look out of place at all. All hands are flat; the hour hand features non of the curvature we see on Rolex models – I have always admired such curvature but this is not a deal breaker whatsoever for me. Given that this hand is narrower than the minute hand in this case then it is possible that any curvature might have made it appear a little too thin. Constructed of highly polished steel, the surface finish is excellent and of course legibility is aided by the use of Super Luminova fill.

The colour of the luminous compound matches that of the dial markers perfectly being a very light green. A small circle of luminous fill adorns the seconds hand and this is positioned correctly with regard to the dial markers. In terms of luminosity at night then the Super Luminova does its job very well, the dial and hands glow bright and long and I am able to read the time well into the early hours with no problem at all.

Overall, the dial and hands execution of the Smiths Everest certainly passes muster with me.

It works very well from all angles but I would reiterate yet again that this is one watch which works immeasurably better in the metal than in photographs. The quality of the dial and hands matches that of the case and crystal and at the price point we are considering I have no complaints at all.

In terms of the watch head itself then that only leaves consideration to be given to what beats away beneath the dial.

Movement

What would make a suitable movement for a watch such as the Smiths Everest? The preference as far as watch aficionados might be concerned would be for a robust automatic calibre of some description. In previous watches, Timefactors has of course used Swiss ETA movements of varying model. Certainly, a movement such as the ETA 2824 would have been very suitable for the Everest. Times however have changed, the supply of such movements is being restricted and before not too long will be throttled by the Swatch Group. In the interim, costs are higher. Undoubtedly, the standard ETA automatics are well proven, reliable and capable of extreme accuracy. But are they the be all and end all? I say not. From my perspective the perception of Swiss automatics being the de facto standard for even basic applications is old hat and almost anachronistic. Indeed times have changed and over the last few years both the Chinese and Japanese have upped the ante and responded to the domination that the Swiss have held within the market for automatic watch movements. Thus, as far back as the mid 1990s Seiko introduced the 4S15 which was of course a remanufacture of a movement from the 1970s – much higher specification than standard calibres with 25 jewels, hacking and handwinding and not forgetting a hi-beat of 28,800 bph. Indeed, Seiko have a wide range of back catalogue movements which they could reintroduce to give the Swiss a run for their money. We are already seeing handwinding, hacking movements (4R36) being introduced to mid range Seiko 5 Sports models and cleverly, Seiko are making such movements available to manufacturers at large. As indeed are Citizen, or more correctly, Miyota.

For reasons possibly of cost and more certainly of supply, the Smiths Everest is equipped with a Miyota movement. I would still at this stage place a Japanese derived mechanical watch movement above a Chinese model though again, that situation is changing with some excellent Chinese calibres becoming available. There is no doubting that Japanese derived movements are proven in terms of longevity and reliability (yes, some may be assembled in China if we are being pernickety) and respect for them has, I feel, grown over the last few years. The standard Miyota automatic movement for many years was of course the 8000 series – this could be found in most, if not all automatic watches to come from the Citizen stable and was basic, but very reliable as expected. Indeed the original Zeno Explorer used such a movement and there were no complaints about such – my most accurate mechanical watch ever was a Citizen using this movement.

Citizen/Miyota have themselves reacted to the ETA supply situation by introducing a new movement to market which was slated to take on the likes of the 2824 – the Calibre 9000 series. This series was first shown at the 2009 Basel Watch Fair and is a very different affair to the 8000 series which had been around for so long (and continues in production). Specifically, it is the Miyota Calibre 9015 which is under consideration and which powers the Smiths Everest. Firstly, the specification:

| Automatic winding: | Yes, by rotor in one direction |

| Handwinding capability: | Yes |

| Hacking (stop second)device: | Yes |

| Diameter: | 26mm |

| Height: | 3.9mm |

| Oscillations: | 28,800 per hour |

| Jewels: | 24 |

| Shock absorber: | Parashock to balance staff |

| Anti-Magnetic Rating: | 4800 A/m |

For an exploded parts drawing, please click here: Citizen/Miyota Calibre 9015 Exploded Diagram

On paper, there would seem to be nothing ‘missing’ from the specification – indeed, the handwinding and hacking combination will certainly please those who missed the former with the Miyota powered Zeno Explorer. The jewel count is healthy at 24 and it is a nice touch to see that the barrel arbour is jewelled, no doubt accounting for 2 of the 24 jewels. Miyota have stayed with the unidirectional automatic winding layout and indeed, one can feel the rotor spinning when it is in the freewheeling direction – this is not obtrusive however, particularly given the heft of the Everest which helps to muffle things somewhat. It comes nowhere near the wobbling that the ETA 7750 is known for. Manually winding the watch is a smooth affair, much smoother than say the ETA 2824 and almost on a par with the higher end ETA 2892. The standard Miyota 9015 is equipped with a date mechanism; one can indeed pull the crown to the date setting position on the Smiths but it would seem that the date wheel and associated mechanics are removed as rotating the crown at this detent does not produce the click of the date turning over.

It should be noted that the combination of a 28,800 bph specification and directly driven centre seconds hand contribute to a nice sweep with none of the judder that was sometimes reported with the 8000 series (this series featured a lower beat rate and indirectly driven centre seconds). Thus, the 9015 is very much a more modern calibre and it would seem that attention has also been given to aesthetics – there is some decoration to the main plate in the form of stripes and everything else seems to be well finished. I must admit that I rather like the use of the three screws to secure the winding rotor – this arrangement reminds me of far more expensive calibres for some reason and although I shall never see it, it is pleasant to know that it is there.

Miyota state an accuracy of -10/+30 a day for the 9015 but in the field accuracy reports appear to be much better than this. Certainly in my case, the Smiths Everest is averaging a +2 seconds per 24 hour gain when the watch is worn continually. I am very pleased with this and such performance corresponds well with the performance I have always experienced with Miyota movements. It is of course relatively early days in respect of both the newly introduced Calibre 9015 and its use in the Smiths Everest.

Regarding the former then I have heard of no reported issues and indeed have heard good reports of accuracy – +2-6 seconds a day not being unusual; in the case of the latter then at this point I am delighted with performance and feel that it is a positive and refreshing thing for the Smiths to be equipped with a new, Japanese movement.

In terms of securing the movement within the case, the Everest employs a hefty metal movement holder to keep the 9015 where it should be and this in itself gives one a feel of how well put together everything is.

I would assume by now that the reader could be under the impression that I am very enthusiastic about this watch.

This is indeed true; the watch head in totalis meets all my expectations of a Timefactors, no, Smiths timepiece. What remains of course is a method of attaching this workhorse to one’s wrist.

Bracelet

As standard, the Everest comes fitted to an Oyster style bracelet which indeed most, if not all predecessors have been too. Is it as simple as that? No. This Oyster bracelet is somewhat more than I expected given the price point of the watch; were the Everest to come as standard on a NATO strap for example, then I would still feel comfortable with its pricing. Suddenly, the value for money aspect of this watch becomes even better.

I am not usually a lover of bracelets on watches; repetitive though I may be, I have to say yet again that I am a lover of NATO straps and indeed tend to fit them to most of my watches. However, in this case, I might just be tempted to allow the Everest to remain on the supplied bracelet. This Oyster style bracelet is of exceptional quality and build. Starting at the watch head, then we have solid end links which fit snugly between the lugs and which match the lug curvature very well indeed. Underneath the end links here is just about enough room to fit a forked spring bar tool for bracelet removal but this should be unnecessary given the thoughtful drilling of the watch lugs.

The bracelet is 22mm at its widest and it tapers to 18mm at the clasp end. In this case, I am pleased to see this taper as it does add some finesse to what is a substantial overall package. Had the bracelet been of parallel design, I think that it may have overpowered the watch head somewhat; to be perfectly honest, I found that I had to measure the width at the clasp – visually the taper looked to be to 20mm. Construction is of solid links which are secured by screws. The centre links are not cast into the bracelet as per cheaper designs, they are separate and in this case, are very slightly thicker than the outer links and thus raised. I find this very attractive and so the contour of the bracelet follows that of the solid end links with their raised centre ‘link’. Referring back to the bracelet screws then it is notable that the bracelet appears to have screws either side; this is not the case – the arrangement is that the threaded pin actually screws into a removable tube which itself has a slotted head. The good news here is that it would be impossible to damage a bracelet link by cross threading it – the whole securing assembly can be removed. Of course, one will need two suitably sized screwdrivers to remove a link but this is a small price to pay for what I feel is an excellent arrangement.

In terms of finish, the tops and bottoms of all links are finely brushed with this finish matching the lug tops extremely closely. The sides of the links are similarly brushed with overall quality being excellent. In terms of sizing, the bracelet (unusually for such) features a half link on each side which in addition to the fine adjustment on the clasp should ensure an absolutely spot on fit for any wearer; this timepiece should fit even the smallest wrists (mine included) given that at the 6 o’clock side there are 2½ removable links and at the 12 o’clock side there are 3½ – these are in addition to the 7 fine adjustment holes on the clasp. The clasp itself is of the double folding type with the hidden mechanism being of solid steel – thankfully, this is not too long, making the bracelet comfortable to wear with no unsightly ‘lumps’ and centralisation of the clasp a snip. The outer clasp is of thick, brushed stainless steel and just to finish things off, is inscribed with the Smiths logo – it is good to see some personalisation here as this truly makes the bracelet seem part of the package.

So, it seems for once that I am happy with a bracelet on a watch! The quality here really is quite excellent, the proportions and heft match the watch head perfectly and the attention to detail is typical Timefactors. That is not to say of course that the watch doesn’t suit other wristwear – the Smiths looks perfectly at home on a NATO strap and indeed very much so on leather. I can’t however find fault with the supplied bracelet as really I can’t with the watch – put these two together and therefore we can decide if Timefactors does indeed have another winner with the Smiths Everest.

Conclusion

Ten years on and I sit with both the Speedbird PRS-1 and the Everest PRS-25 in front of me. Having lived with the Everest for a week or so now I have come to appreciate what it is. It certainly pays homage to watches before it yet it has a touch of indivduality that makes it stand out from the rest. This individuality can, in my opinion only be appreciated by holding the watch, wearing it and just living with it. I have touched on value for money during the review but haven’t mentioned the price – at its introduction, the Smiths Everest costs GBP £225.00 direct from Timefactors. Given the design, the attention to detail and above all else the quality of this wristwatch I do find it hard to believe that it can be offered at such a value for money figure.

As a wristwatch, it is practical, attractive, looks ‘right’ and I have no reason to doubt its robustness or longevity – the sum of its components I am certain will ensure these things. From where I am sat it is undoubtedly a winner and more than worthy of bearing the name ‘Smiths’. Therefore, I highly recommend the Smiths Everest PRS-25 and congatulate Timefactors on having produced it.

As the reader may surmise, I have truly fallen in love with this wristwatch and so it takes its place next to the Speedbird which of course was the one that started the ‘journey through Timefactors’ for me all those years ago; two 007s side by side. I predict that in another ten years I will look nostalgically at both these watches and relive the memories with which I shall associate them.

Postscript…

It looks good on a NATO too!

Available exclusively from TIMEFACTORS (www.timefactors.com)

A huge thanks goes to those who have allowed me to keep my camera in the cupboard (yet again) and given me permission to use their excellent images: